Keeping track of history: How Riverhead’s station fed New York

Before refrigerated trucks and interstate highways, freshly dug potatoes from Riverhead could reach Brooklyn dinner tables within 48 hours.

That was in 1844, when the Long Island Rail Road extended its line to Riverhead.

The new spur turned the East End from an isolated agricultural outpost into the bread-and-veggie-basket of New York. In addition to its geographical centrality, Riverhead had been Suffolk County’s seat of government since 1727, making it the natural choice for a rail center.

“We were an agricultural economy, we were a seafaring economy,” said Don Fisher, president of the Railroad Museum of Long Island. “Riverhead became the center and was physically, geographically, and certainly population-wise, the center of our county, and became the hub for our government. Everybody moved everything by boat before the railroad got here.”

Populations on the East End at that time were concentrated along the shorelines. The farmers who did begin to cultivate the Forks had good soil for growing all kinds of crops, including the potatoes and cauliflower the region was known for. And before the experimental farms, farmers didn’t believe that they could go into the Pine Barrens.

Because of the railroad, the Forks could now supply the rest of Long Island, which at that time included Brooklyn, and Manhattan with fresh produce. Farmers could take their products and put them on a train into cold cars, and have them reach population centers often within a day or two after harvest.

Farm produce coming into Riverhead went through the auction houses, where it was bought by brokers and then put on the railroad cars to be transported out of the area. These brokers sold to supermarkets and others — usually within two days of the vegetables being dug up.

“That stimulated everything in farming out here, because farmers now weren’t just growing for themselves and Suffolk County,” Mr. Fisher said. “They had a way, with the railroad, to be able to ship more and more produce, putting more and more acreage into production.”

The system proved remarkably efficient for its time.

“We had this thing licked. We had it down, farm to table,” he said. “The tables were in New York City. The tables were the people living in the tenements along the East River, the people living in Brooklyn.”

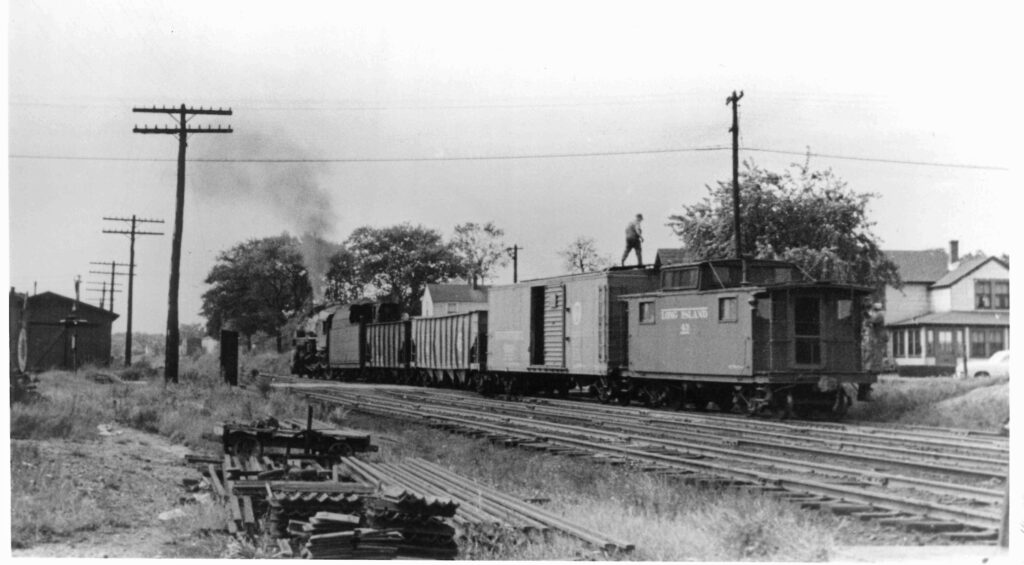

The LIRR used special cars lined with ice, known as reefers. These cars were filled from above via a hopper at the ice plant. There were vents at either end to circulate air, and melted ice and condensation would run out onto the track.

Riverhead yard also had a special engine called a hostler to move cars through a complicated network of sidings. Each siding had an assigned purpose, and a crew could kick three boxcars off so they went into Brooklyn.

“The actual work of moving all of this produce was time sensitive, laborious and it required resources from the railroad to make it work,” Mr. Fisher said. “One of those resources, we got our own locomotive.”

At first, the LIRR extension did not result in a population boom on the East End. Because the land was so productive, the properties proved more valuable for farming. Keeping those fields open for cultivation produced more wealth than dividing them for houses.

“The railroad coming here, creating a better economy for the farmers, limited the amount of people that were going to come out here at the time and build houses and live here, because the property was so valuable for farming,” Mr. Fisher said.

It wasn’t until after World War II that the railroad, combined with the highways, helped supercharge Long Island’s population growth as developments like Levittown blossomed. Before the war, bulk produce dominated traffic heading west from the East End.

It wasn’t only produce leaving the East End headed west that made use of Riverhead Station. Freight was also shipped east. Anything big, bulky or heavy was easier to ship via rail.

LILCO, the predecessor to LIPA, had two sidings in Riverhead because their poles and transformers came out on the train. Farm equipment was often shipped on flatcars. There were also smaller items that came via post cars and baggage cars on the railroad. Mail order items from catalogs would be left in the freight house for someone to pick up in their wagon and take home.

“We think about things that come to us today on UPS, FedEx, Postal Service — those things came out in special cars, baggage cars, railroad post office cars, and they went to the train station or to the little freight house,” said Mr. Fisher.

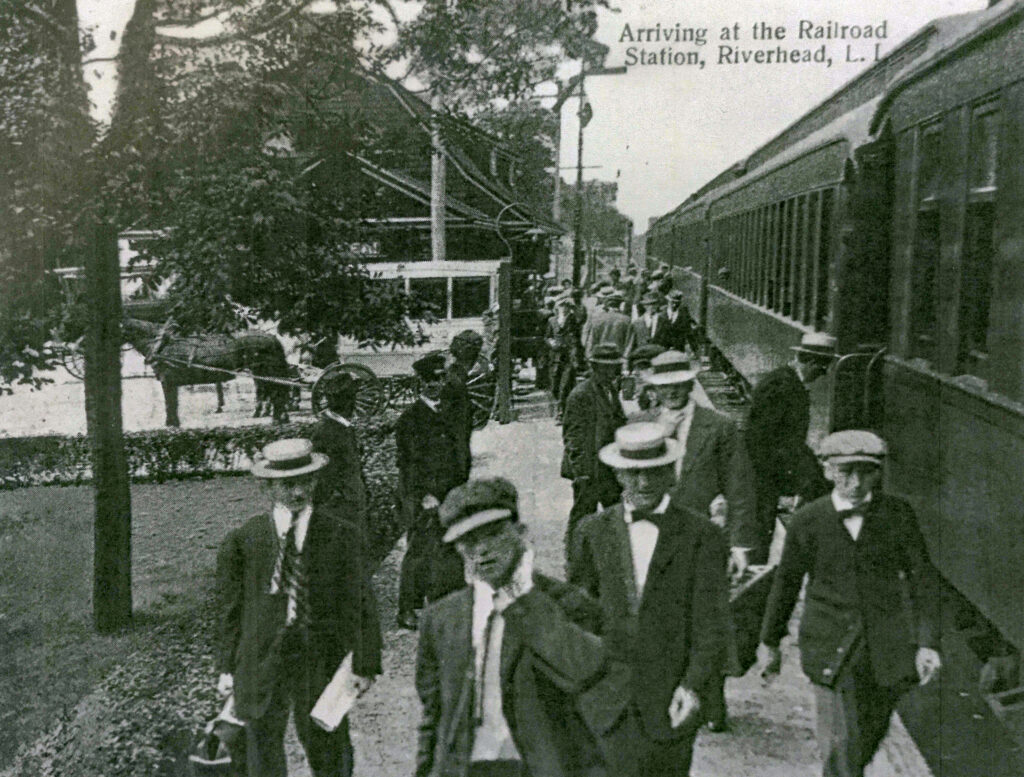

Because Riverhead is the county seat, the railroad also made it easier for politicians to attend meetings. Instead of taking a week to trek out to Riverhead for monthly business, it was a matter of days by train.

Before Suffolk County had a Legislature, it was controlled by supervisors of the 10 towns and they would meet in Riverhead once a month. With the railroad, they could get on the train at 6 in the morning and be there by 9 a.m. They could meet all day, stay overnight and be home the next day.

“Not only was this great for the people that were doing the work, but it saved government money,” Mr. Fisher explained.

Instead of putting politicians up for four or five nights in Riverhead, they only had to stay one night.

“We were saving taxpayers’ dollars,” he said.

Today, the LIRR still has a stop at Riverhead, but the old railway center serves as the home of the Railroad Museum of Long Island.